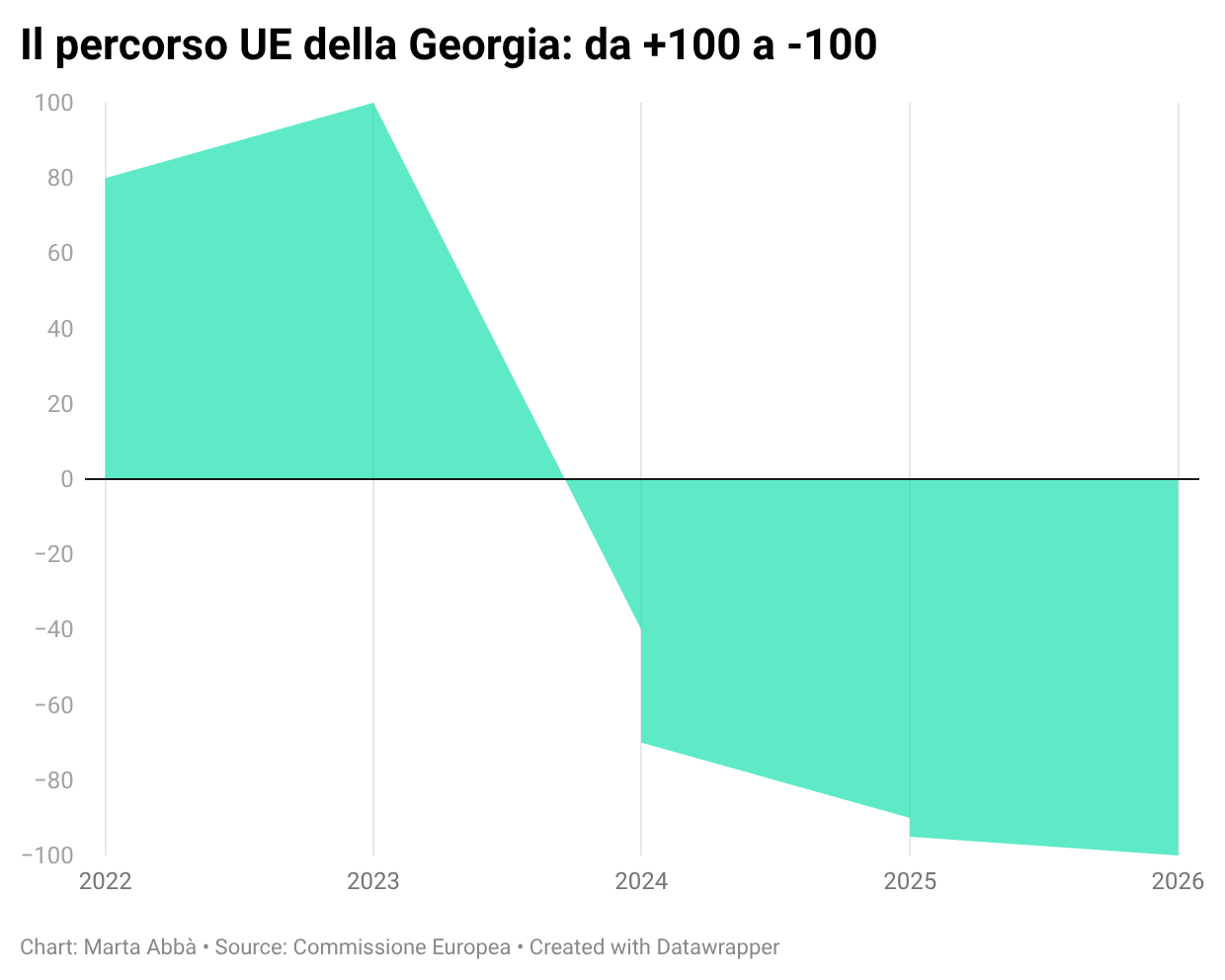

The European Commission now considers Georgia to be “only nominally a candidate country”. In 2024, the European Council concluded that the process of accession to the European Union had effectively been halted. The situation worsened in November 2024, when the Georgian authorities decided not to pursue the opening of negotiations, confirming their reversal of the policies of previous governments and the European aspirations of the majority of the Georgian people. (In December 2025, Startupbusiness supported the Touch Summit, the main technology event held in the Georgian capital Tbilisi, with the aim of helping to strengthen the relations that the most pro-European part of the country is maintaining with international ecosystems, ed.).

According to Brussels, since then there has been “a serious democratic backsliding characterised by a rapid erosion of the rule of law and restrictions on fundamental rights”, with legislation limiting civic space, undermining freedom of expression and violating the principle of non-discrimination. The Commission stresses that the Georgian authorities must “urgently reverse their democratic backsliding” and undertake concrete reforms, supported by cross-party cooperation and civic engagement.

From an environmental perspective, the Commission notes that Georgia’s administrative capacity ‘remains low, affecting the country’s ability to implement the climate acquis’. Despite some rationalisation efforts, human and financial resources in this area need to be substantially strengthened. Georgia is only partially aligned with the EU acquis on horizontal environmental legislation, and the full list of necessary reforms is outlined in the latest enlargement report.

The European Union’s response has been clear: since the beginning of the political crisis, Brussels has cut direct assistance to the Georgian authorities by more than €120 million, suspended €30 million in support for 2024 through the European Peace Facility, and does not plan any support measures for 2025. However, the Union is tripling its support for civil society and independent media, increasing the allocation from €5 million to €15 million.

The crisis of the environmental movement

The political upheaval of 2024 dealt a severe blow to the Georgian environmental movement. The ruling Georgian Dream party first introduced the foreign agents law, then monopolised power after parliamentary elections that the European Union did not recognise. Mass civil protests, which also involved environmental activists, continue but have become less widespread, while various forms of repression have begun with the first political prisoners and many non-governmental organisations on the verge of liquidation.

Many organisations have refused to register under the foreign agents law, which would complicate their work and stigmatise the organisations, undermining the trust of the local population. However, they cannot operate without official registration. As one representative of the environmental movement, who wished to remain anonymous, noted, “it feels like a return to the Soviet Union, where the word ‘agent’ can also be interpreted as ‘spy’.”

The law jeopardises any funding from abroad. Large funds are avoiding working with Georgian organisations, which are completing their projects and closing down. This is damaging areas that have been the prerogative of non-governmental organisations since the 1990s. By 2025, there is already a clear retreat in environmental and climate policy: the government has begun to lower environmental protection requirements and standards, or simply to give up nature conservation areas for construction.

Concrete environmental issues

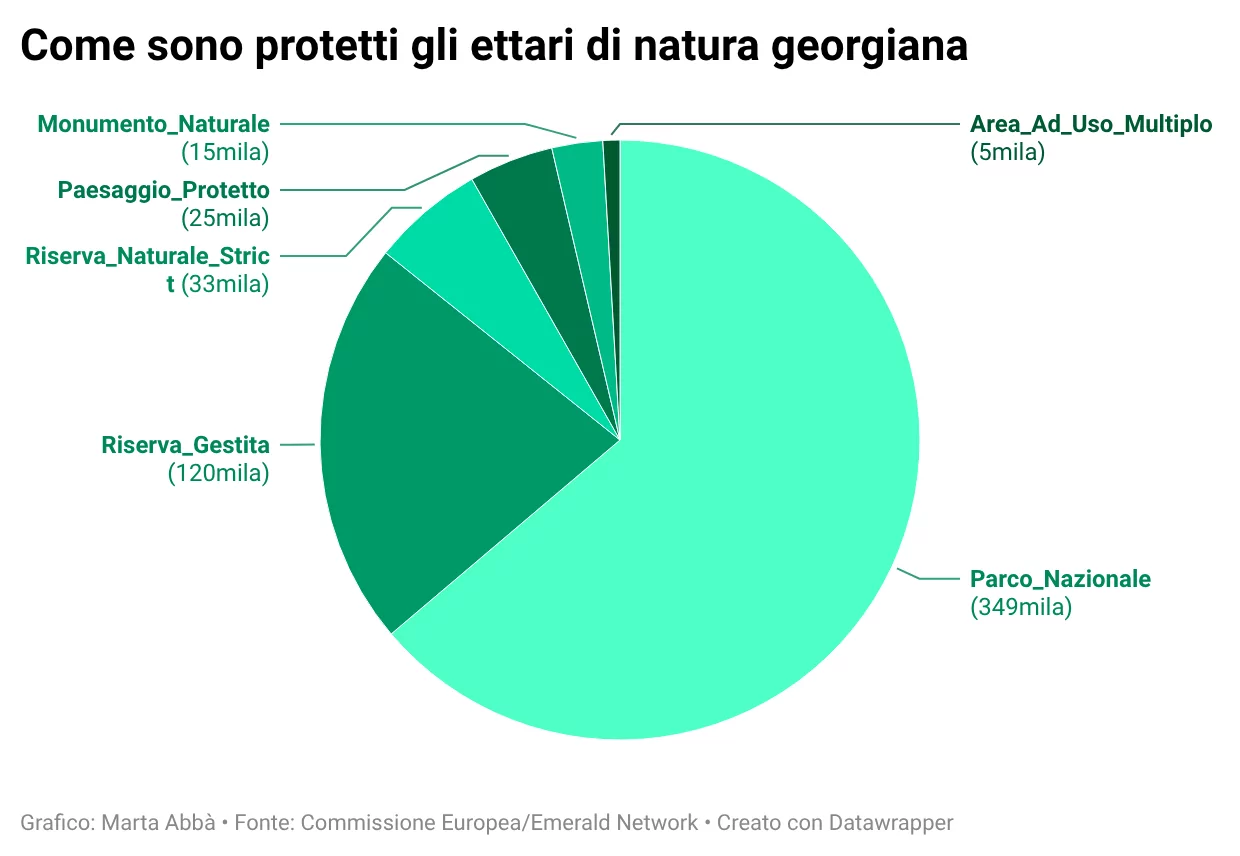

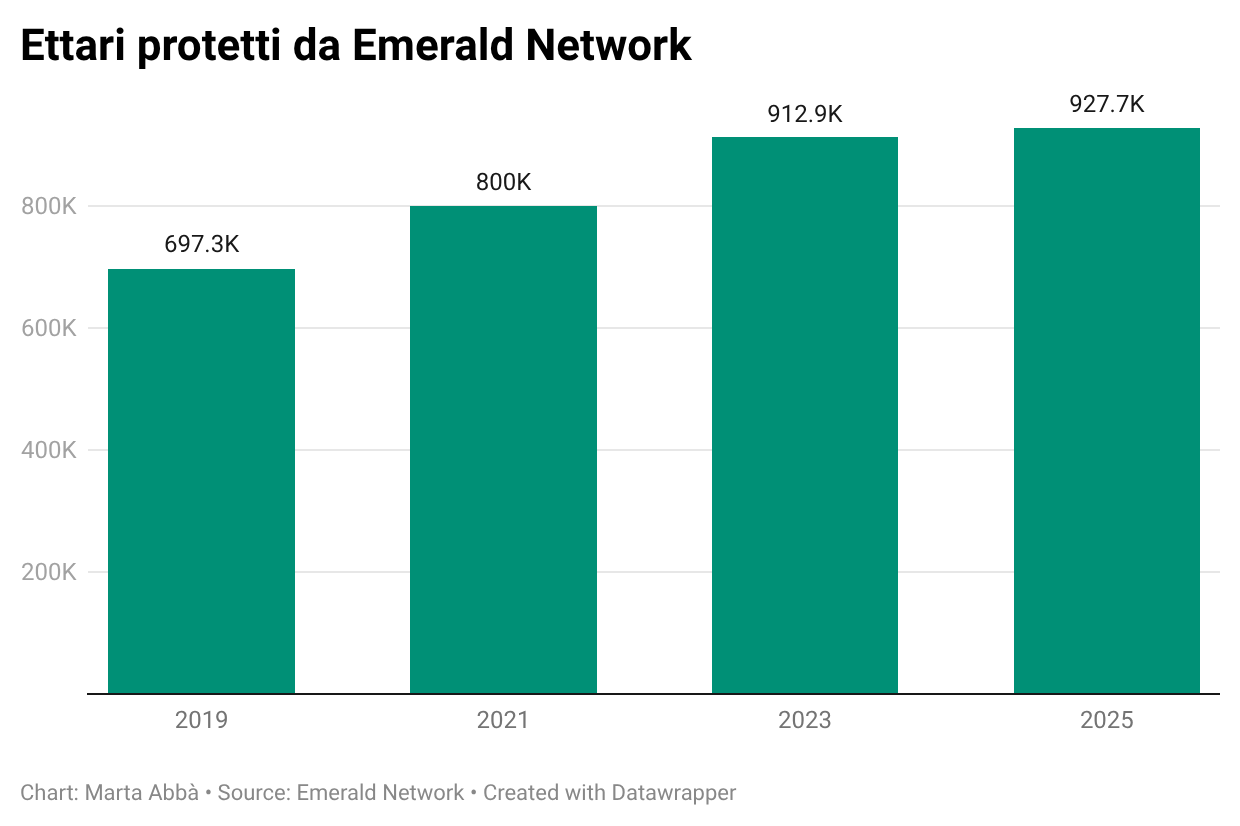

One of the most emblematic cases is represented by the plans of the Arab company Eagle Hills to build in the Chorokhi River delta and Krtsanisi Park near Tbilisi. The Chorokhi delta has Emerald Network environmental protection status and is a key bird migration area through the Transcaucasian corridor. Zura Gurgenidze of the Sabuko organisation calls it ‘one of the most important areas in terms of biodiversity conservation’. The construction ‘will not only close off this area, but destroy it’, with potentially catastrophic and cross-border consequences.

The Black Sea coast is turning into one big construction site. The building of a complex of artificial islands in the Batumi area has already caused the release of fuel oil left on the seabed since Soviet times, harming water birds. Development is proceeding without adequate infrastructure: some of the wastewater still flows directly into the sea, despite treatment projects funded by the European Union. Arab and Turkish investors, the main financiers of the construction, give lower priority to high environmental and climate standards.

The melting of glaciers, linked to climate change, has already caused a tragedy in Shovi with over thirty deaths. The first scientific inventory of the rocky glaciers of the Greater Caucasus was only carried out in 2023, the year of the tragedy. Research requires international cooperation, with European countries representing the most promising direction for the exchange of knowledge.

The disappearance of groundwater is another pressing issue. A 2022 study showed that around half of the rural population does not have access to drinking water. In 2025, there were severe fluctuations from drought to flooding, caused by climate change and intensive agriculture. The government’s plans to actively build hydroelectric power stations risk further disrupting river flows.

Prospects

The Georgian environmental movement has essentially been told to focus solely on non-political activities: growing organic produce, helping remote villages, holding conferences. Protests against development projects, such as the one against construction on the site of the former racecourse in Tbilisi, have been unsuccessful. The movement is being pushed out of the political arena, in a process comparable to the situation in Belarus and Russia.

Small projects such as Green Guria continue with the support of the European Union and organisations such as CENN (Caucasus Environmental NGO Network). However, the criminalisation of protest activities and the reduction of the legal framework are major concerns. Georgia, surrounded by the Black Sea and the Caucasus Mountains, is a bird migration corridor, an important agricultural region and the home of wine. Its sustainable development is an integral part of European environmental security. Without support for the Georgian environmental movement, there is a risk not only of losing the country’s natural environment, but also of facing a serious environmental catastrophe in the Caucasus. (The photo shows a glimpse of the Georgian coast on the Black Sea.)

This article was created as part of the PULSE Thematic Networks, a European initiative supporting cross-border journalistic collaborations.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ©